Corruption in Kenya is becoming increasingly entrenched rather than episodic, according to the 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), which shows the country continuing to struggle with weak accountability, stalled reforms, and declining public trust amid a broader governance downturn across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Kenya’s score fell to 30 out of 100 in 2025, extending a long pattern of stagnation and decline. The drop places the country firmly below the global average of 42 and under the Sub-Saharan Africa regional average of 32, reinforcing concerns that anti-corruption efforts have yet to yield sustainable progress.

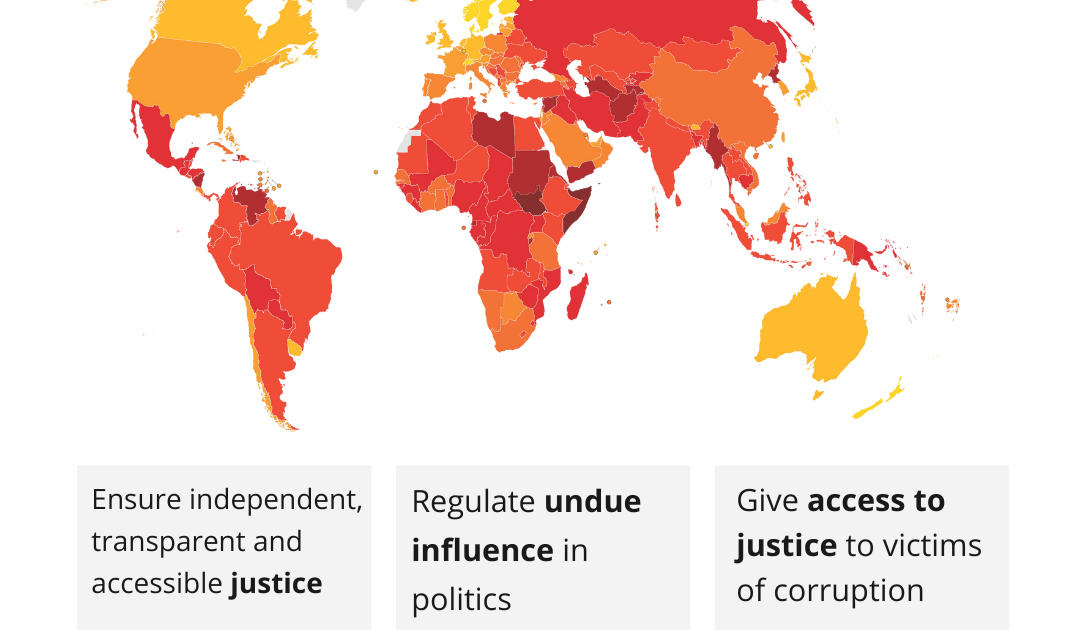

Published annually by Transparency International, the CPI ranks 182 countries and territories based on perceived levels of public-sector corruption. Scores range from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). A score below 50 is widely viewed as a red flag for serious governance weaknesses.

Founded in 1993, Transparency International operates in more than 100 countries to expose corruption and promote transparency, accountability, and integrity in public life. The CPI is regarded globally as a key benchmark used by governments, investors, and civil society to assess governance standards.

For many Kenyans, the latest figures validate lived realities: public funds continue to leak through procurement scandals and mismanagement, accountability mechanisms remain fragile, and justice is often perceived as selective.

“Kenya’s latest score indicates that corruption is no longer a series of isolated incidents; rather, it has evolved into a sophisticated, resilient system that has permeated all levels of society and government,” said Sheila Masinde, Executive Director of Transparency International Kenya.

“It is undermining democracy, the rule of law, good governance, transparency, and accountability,” she added.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the lowest-scoring region globally. Of its 49 countries, only Seychelles (68), Cape Verde, Botswana, and Rwanda scored above 50. Since 2012, ten countries in the region have deteriorated significantly, while only seven have shown marked improvement.

At the bottom of the global scale are Somalia and South Sudan, each scoring 9, where protracted conflict, fragile institutions, and limited oversight create fertile ground for unchecked corruption. By contrast, Seychelles’ performance demonstrates that strong institutions, effective judicial enforcement, and political will can produce measurable gains.

Kenya sits in the region’s lower tier, slightly ahead of Uganda and Burundi but far below top performers. Over the past 13 years, its CPI score has fluctuated between 25 and 33, suggesting that periodic reform initiatives have not translated into systemic change.

Analysts note that Kenya’s challenge lies less in legislative gaps and more in enforcement failures. The country has robust constitutional provisions on leadership and integrity, as well as institutions mandated to investigate and prosecute corruption. However, few high-profile convictions have been secured.

“With few high-profile convictions in corruption cases, coupled with a disturbing pattern of case withdrawals and weak prosecution, many offenders have escaped punishment,” Masinde said. “This has perpetuated impunity.”

The consequences are tangible. Mismanaged or siphoned public funds leave hospitals under-equipped, classrooms overcrowded, roads incomplete, and social protection programmes underfunded. Citizens bear the burden through diminished public services, rising costs of living, and in some cases, informal payments required to access essential services.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, corruption in public finance has widened inequality and fueled political alienation. Young people, in particular, are increasingly vocal about governance failures. In several low-scoring countries, including Nepal and Peru, Gen Z-led protests in 2025 triggered significant political reckonings. While Kenya has not witnessed comparable unrest, public frustration over economic hardship and perceived elite impunity continues to grow.

The 2025 CPI also dispels the notion that corruption is primarily a developing-world problem. The global average score fell to 42, its lowest level in more than a decade, reflecting backsliding even among established democracies.

Countries such as the United States (64), United Kingdom (70), France (66), and Sweden (80) recorded declines, attributed to shrinking civic space, weakened checks and balances, and the growing influence of money in politics.

“This shows that corruption is not inevitable, but neither is progress guaranteed,” said François Valérian, Chair of Transparency International’s international board. “There is a clear blueprint for how to hold power to account: through democratic processes, independent oversight, and a free and open civil society.”

For Transparency International Kenya, the path forward requires structural reforms rather than symbolic gestures. The organization argues that political promises and sporadic arrests are insufficient to reverse the downward trajectory.

Its recommendations include strengthening protections for whistleblowers and investigative journalists, tightening campaign finance regulations ahead of the 2027 general elections, and fully enforcing constitutional provisions on leadership and integrity.

Crucially, it calls for genuine operational independence and adequate resourcing of institutions responsible for investigating, prosecuting, and adjudicating corruption cases. Without such independence, even the strongest legal frameworks risk remaining aspirational.

Although the CPI measures perceptions rather than documented instances of corruption, those perceptions carry significant weight. They influence investor confidence, shape international partnerships, and affect the legitimacy of state institutions.

For Kenya, the 2025 index sends a stark warning: unless corruption is addressed as a deeply embedded system rather than a succession of scandals, the country risks entrenching a cycle in which power serves private interests, accountability remains elusive, and public trust continues to erode.

By Grace Naishoo