A severe shortage of nurses in Kenyan hospitals’ newborn units (NBUs) is leaving sick and premature babies with only a fraction of the care they need, despite significant investments in modern medical technology, a new study has revealed.

The (Harnessing Innovation in Global Health for Quality Care) HIGH-Q study, conducted by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)-Wellcome Trust in collaboration with the Kenya Paediatric Research Consortium (KEPRECON) and the University of Oxford, found that in some facilities, nurses care for more than 25 newborns during a single 12-hour shift, with each baby receiving an average of just 30 minutes of attention—far below international standards.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNICEF, critically ill newborns should receive continuous monitoring with nurse-to-baby ratios of 1:1 or 1:2, while even stable newborns required frequent observation.

Researchers warn that the staffing crisis undermines the benefits of new equipment and threatens Kenya’s ability to meet its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of reducing neonatal deaths to below 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030. Currently, the national average stands at 22 per 1,000 live births.

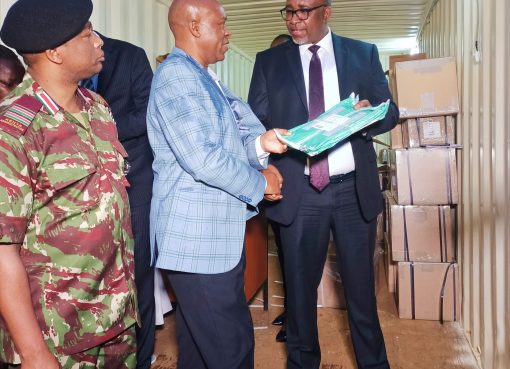

In his speech during the HIGH-Q Media Breakfast and Stakeholder Dissemination meeting in Nairobi on Friday, KEMRI Director General Prof. Elijah Songok described the findings as a wake-up call—but one that is already prompting action.

“In Kenya, reducing neonatal mortality from an average of 22/1000 live births is part of the government’s efforts to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and key to this is the role of nursing in neonatal care. Workforce development is central to building a resilient health system. We must strengthen our workforce, improve hospital environments, and ensure every newborn receives the quality care they deserve. The good news is that the government, through the Ministry of Health, is taking decisive steps using the very solutions identified by this research,” he said.

The study also highlighted the emotional toll on mothers, many of whom reported stress, stigma, and confusion due to poor communication and lack of support from overwhelmed nurses.

Staff burnout, overcrowded wards, and poorly designed facilities were also found to compromise hygiene, safety, and patient dignity.

“Whilst better technologies can improve neonatal care, a key factor in their successful use is nurses, who provide care for sick babies 24 hours every day they are in hospital. Nurses remain the primary providers of essential care, monitoring, feeding, administering medication, hygiene, and emergency interventions. In low-resource settings like Kenya, severe nurse shortages and high patient loads adversely affect delivery of this care,” said Dr. Dorothy Oluoch, Social Science Research Fellow, KEMRI Wellcome Trust.

“For the first time, we have a detailed understanding of the challenges nurses face and how extreme workloads affect their ability to care for sick newborns,” added Prof. Mike English, Principal Investigator of the study. “It will be hard to advance quality of care without improving nurse staffing and the design of newborn wards.”

The Ministry of Health, in collaboration with county governments, KEMRI, KEPRECON, and international partners, is already implementing evidence-based solutions identified in the HIGH-Q study.

“This study provides practical, evidence-based solutions that the Ministry of Health and counties could implement immediately. From increasing nurse staffing and institutionalising ward assistants to redesigning newborn units, these measures will improve care for babies and support nurses in delivering it effectively,” said Prof. Fred Were, Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health specialising in Newborn Medicine and Senior PI of the HIGH-Q project.

The HIGH-Q project piloted three interventions: hiring extra nurses, introducing ward assistants, and providing communication skills training, all of which improved teamwork, hygiene, emotional support for mothers, and nurse-parent interactions.

“Researchers recommend scaling up these interventions alongside major investments in recruitment and infrastructure,” added Dr. Michuki Maina from the research team.

The study covered eight county hospitals within the Clinical Information Network where the Newborn Essential Solutions and Technologies (NEST 360°) programme has been rolled out and was funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR).

With these findings now in the hands of policymakers, health leaders hope the combined efforts of government, partners, and frontline health workers will transform neonatal care and give every newborn in Kenya the best possible start in life.

By Violet Otindo