It’s a presidential function at Uhuru Park in 1982. The president is the late Daniel Arap Moi, and a battery of journalists is eager to document the event. Security agents mingle with the crowd and press, alert to every movement.

Among them is cameraman Henry Bwoka, who unwittingly commits what could have been a grave verbal misstep. He urges his soundman to prepare.

“Let me know when you’re ready so that when the president begins delivering his speech, I shoot him,” he says. Instantly, a sharp-eared, smartly dressed man whirls around and demands clarification: “Unasema nini wewe? (What did you say?)”

Bwoka is jolted to his senses and quickly recants, “No! I mean filming!”

At that time, it wasn’t far-fetched to imagine a few young film students animatedly discussing magazines, loading, cartridges — and, as in Bwoka’s case, shooting. In the tense political climate of the early 1980s, such terms could easily be misconstrued. Security agents were ever-watchful for suspected subversives, and careless language could earn one a long interrogation in a nearby installation.

Several underground movements, such as Mwakenya, had been outlawed. Words had to be weighed carefully, lest one be mistaken for a dissident who deserved to be “locked out of sight.”

It often fell to instructors to rescue anxious film trainees from overzealous officers, explaining that their jargon had nothing to do with ballistics. Indeed, many expressions used in filmmaking took years to be understood beyond the industry.

“The shooting ratio for film was 1:1,” Bwoka recalls. “Each action was to be shot only once — you either got it or never.” In a sense, he adds with a wry smile, a cameraman had to be a marksman.

Mbarack Ambe, now a lecturer at the Technical University of Kenya, was a producer in the 1980s and 1990s at the Voice of Kenya (VoK). He reminisces, “Deletion was unknown. These days you shoot, preview, and delete if the image isn’t satisfactory. Back then, you lived with your mistakes.”

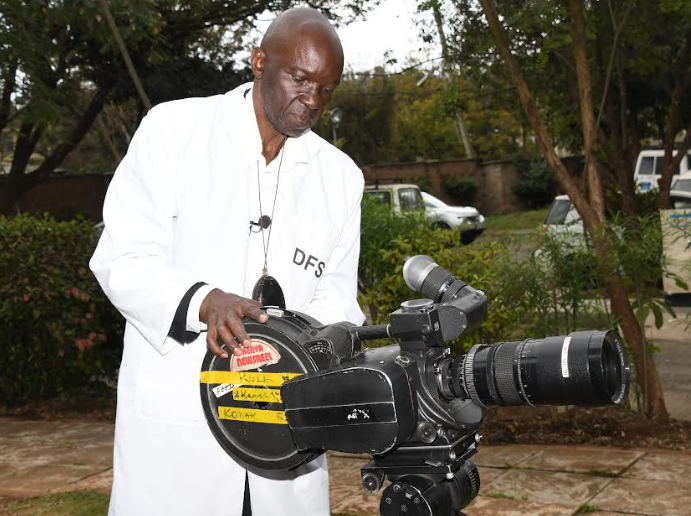

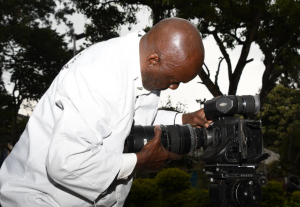

Bwoka, now a farmer in Bungoma County, retired from the Ministry of Information in 2016 after more than three decades behind the camera. He still occasionally freelances, though he notes with some resignation that what most colleges now call “film production” is, in truth, video or television production. “The original definition of film explains why,” he observes.

What Film Really Is

Film, he explains, is a thin, flexible strip of material coated with a light-sensitive emulsion—silver halides—on one side, and a gelatinous base on the other. The emulsion could be silver bromide, silver chloride, or a combination of both (silver bromochloride).

Older generations of filmmakers referred to film as celluloid to distinguish it from the later entrant, video. What is now taught in most institutions uses an entirely different medium of image registration.

Bwoka joined the film industry in the late 1970s as a trainee at the Kenya Institute of Mass Communication (KIMC), where the Film Production Training Department had been established by Germany’s Friedrich Ebert Foundation. He was part of the second intake, from 1979 to 1981.

Five core classes covered production techniques, camera work, sound, editing, and laboratory processes. He vividly recalls being rotated through each section — a foundation that furnished him with a broad mastery of the craft.

KIMC was fondly described then as the only college of its kind south of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo. During Bwoka’s time, each class had no more than ten trainees of various nationalities. His camera class, for instance, had two Kenyans and three others from Zambia, Ethiopia, and The Gambia.

Today, the market is flooded with countless brands and models of digital video cameras, but back then, training focused on 16mm and 35mm film gauges.

“It’s unfair to compare film with video,” Bwoka insists. “Film is superior. The celluloid used to manufacture raw film stock is special — the picture quality is incredibly high.”

He maintains that film cameras required only minor servicing, whereas video cameras had multiple parts that wore out easily.

“A 35mm camera in the 1990s cost about KSh 50 million,” he recalls. “Hollywood has stuck to film for a reason.”

When film reigned supreme, a cameraman referred exclusively to one who operated a motion-picture camera, while photographers dealt with still images. Today, the boundaries have blurred, and the Director of Photography (DOP) in a motion-picture production now “calls the shots.”

Bwoka was trained to operate Arriflex 35ST and 35BL cameras, both released in 1972 and famed for their durability. They dominated production for nearly two decades.

“The 35BL weighed about 20 kilograms with a standard lens,” he remembers. “The tripod alone was 12 kilos — sturdy as a rock. A smaller one would have been like an elephant sitting on a pickup truck,” he laughs. “That’s why it was important to have a friendly sound operator — to help carry it.”

Film Footage

The final iteration of that camera series, the 35BL4S, was released in 1989 — and Bwoka’s career outlived its production run.

The most renowned manufacturers of raw film stock were Eastman Kodak (USA), Fuji (Japan), and Agfa Gevaert (Germany), with Kodak dominating the market.

“One roll of 35mm, 400 feet, around 2000 cost about KSh 20,000,” he recalls. “Imagine going out with two rolls and messing one up!”

Once raw film was exposed to light, it was ruined — “fogged,” as filmmakers would say. Unless processed promptly, even exposed stock had to be handled with utmost care.

Because of this sensitivity, loading film into a magazine had to be done in total darkness — either in a darkroom or using a black loading bag. The same procedure was used for unloading exposed rolls into lightproof cans.

After loading, Bwoka would mount the magazine onto the camera, engaging the transport claws that hooked into the film’s sprocket holes as it ran through the gate, winding onto a take-up spool.

Picture and sound could be recorded separately or jointly, depending on the camera. During his first three months of training, Bwoka was assigned to sound.

“We used to record with the Nagra 4.2, powered by twelve size-D batteries,” he recalls. “It was reel-to-reel, and the quality was excellent.”

He later specialized in camera work while his sound operator handled audio. Sometimes, the two were connected by a synchronization cable.

Each take began with a clapperboard, labeled with the date, scene, and roll number. When clapped, the visual cue of contact matched the audio click during post-production, allowing the two to be synchronized.

Motion Perception

Instead of cables, some crews used electronic sync gadgets installed in both the camera and the Nagra recorder. Retired soundman Lawrence Musyoka explains,

“There was the double-system, where pictures and sound were recorded separately. A signal was sent to the camera to trigger synchronous recording.”

This, he notes, was exactly what Bwoka and his colleague used that day at Uhuru Park — just before “shooting” the president.

Automatic settings didn’t exist on 35mm cameras; everything was manual. Before each take, Bwoka used a hand-held exposure meter to measure the amount of light falling on the subject.

Calibration depended on the film’s sensitivity, measured in ASA (American Standards Association).

“We had high-speed material for indoor work and low-speed for outdoors,” he explains. “The light meter guided the aperture setting. A 200 ASA film was less sensitive than a 500 ASA.”

He adds that though we call them motion pictures, movement is merely an illusion. Film taught him that truth better than anything else.

The camera he used shot at 24 frames per second (fps) — meaning 24 still pictures projected per second created the illusion of motion.

“If I recorded 12 frames per second, that would give fast motion,” he explains. “To get slow motion, I’d shoot at 50 frames per second.”

For 16mm film, he used the Bolex series — ideal for documentaries and room projection. The 35mm gauge, by contrast, was meant for large-screen cinema projection.

Cinemas such as Kenya, Nairobi, 20th Century, Cameo, Odeon, and Fox Drive-In once had their silver screens illuminated by his 12-minute newsreels — The Kenya Newsreel.

“I used to travel abroad to cover presidential functions for posterity,” he recalls, referring to President Moi’s tenure.

Film Processing

By then, it was clear that Bwoka’s “shooting” was harmless. “The presidential team would film for TV news, and my colleague and I on 35mm for the archives,” he explains. He fondly recalls an assignment in Swaziland.

“I was the only one with a 35mm camera,” he reminisces. “A white journalist came over, patted my back, and said, ‘Gentleman, you’re the only one here with a camera. The rest have toys.’ I knew exactly what he meant — and just told him, ‘Thank you.’”

After filming came the long, delicate process of post-production. The images were latent — invisible until processed. KIMC had one of only three 16mm film-processing laboratories in Kenya; the other two were at the national broadcasting houses in Nairobi and Mombasa.

Ambe recalls one dramatic Safari Rally shoot. “A racing car veered off the track and ploughed into a mound,” he recounts. “We stopped filming and rushed the reel to the lab — we thought we had a golden shot.”

But the lab technician, Sylvester Okondo (now deceased), had bad news.

“He told us, ‘I can’t see anything,’” Ambe recalls with a chuckle. “When we previewed, there was only a flash of light — we’d missed the shot entirely. Nobody dared tell the newsroom. We just quietly went home, disappointed.”

Kenya never had a 35mm laboratory, so Bwoka’s footage and soundtracks had to be processed abroad — first in Austria, later in Great Britain.

“In 1985, my colleague and I visited the Austrian lab,” he reminisces. “Editing, sound laying, and commentary were done there. The two-week trip was fascinating.”

By 2000, the Kenya Newsreel had ceased operations due to prohibitive costs. The rise of cheaper, tape-based camcorders only hastened film’s decline.

“I was still glued to film,” Bwoka admits, “but I had no choice but to join the video group.”

In Africa, the last countries to hold out on film were Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia. And though film has long been shot dead by video in Kenya, the medium remains firmly etched in Henry Bwoka’s memory — a relic of artistry, patience, and light.

By William Inganga