Former film cameraman Henry Bwoka is not the only one lamenting what he calls “the death of film in Kenya.” His colleague and fellow retiree, John Wambulwa, a former sound instructor at the Kenya Institute of Mass Communication (KIMC), sings the same dirge from his rural home in Mapera village, Tongaren Constituency.

Wambulwa and Bwoka trained together between 1979 and 1981, in a pioneering programme funded by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation of Germany. The training began at the then Voice of Kenya (VoK) and at Mombasa House near Jeevanjee Gardens before later relocating to KIMC.

Today, Wambulwa believes Kenya abandoned a noble craft when video overtook film.

“We have gone the wrong direction,” he says. “Sound in itself was an art.”

He finds it troubling that anyone who merely records audio can now call themselves a sound technician.

According to him, film-era sound recordists were not just operators—they were creators.

“You visualized the sound and music to be used in a production. You could even advise a producer on which musician to record for the soundtrack.”

A Stirring Reminder in the U.S.

In November 2022, while visiting his daughter in the United States—a film enthusiast trained at KIMC’s Film Production Training Department—Wambulwa was asked:

“Do you still enjoy watching films the way you used to?”

His enthusiastic “yes” earned him a trip to a cinema.

When the silver screen lit up, the memories flooded back.

“I was a regular visitor to the theatres. Cinema halls there are filled!” he says.

He remembers the glory days of Kenyan cinema at Kenya Cinema, Nairobi Cinema, and 20th Century.

“You sat there, watched, and felt that you were right where the action was.”

Foreign film crews frequently shot on Kenyan locations, and he often accompanied them. Seeing those locations again in the final films was always thrilling.

He also recalls the mobile cinema vans that travelled the country showing films in open-air venues.

“They always started with Kenya Newsreel. You would see something interesting… maybe wildlife.”

A Life in Training

Wambulwa retired in 2016 from the Ministry of Information and Communications after 37 years of service. He remembers his classmates vividly:

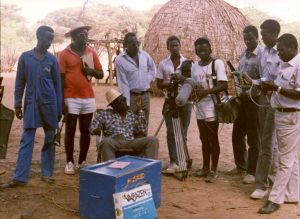

Jane Lusabe (now retired, living in Bungoma), Johnson Barasa (former cameraman at KTN and SABC), and Pius Kilaiti of KTN. Their class also included students from Gambia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Zanzibar.

At KIMC, film production training comprised camera, sound, editing, laboratory, and production techniques. Each area had strict entry requirements:

- Sound & Camera: strong math and physics (especially at A-level)

- Editing: strong English and geography

- Laboratory: chemistry was essential

The first 2–3 months were spent in general orientation across all departments to foster teamwork.

When his course ended, German trainers wanted locals to take over. Students from each specialty were selected for further instructor training—Wambulwa was chosen for sound.

He went on to teach countless sound classes, each intake admitting only 10 students every two or three years. KIMC admitted up to 30 students each in TV, radio, and mass communication.

“The number of students I taught is enormous,” he says proudly.

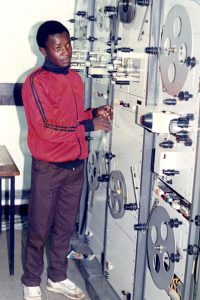

(Photo: Courtesy Danson Siminyu)

One of them was Danson Siminyu, now at the Presidential Music Commission, who studied under him from 1989–1991.

Siminyu describes him as part of “a generation of well-equipped trainers” who nurtured many of the practitioners that shaped Kenya’s film landscape.

“Whether it was acoustics, editing, microphone placement, filtering, camouflaging or mixing—Mr. Wambulwa delivered each with finesse.”

He calls him a “mobile sound textbook.”

Wambulwa supervised Siminyu’s final project, Ngikaala, a documentary on the camel economy in Turkana.

The Era of Sound Recorders and Film Cameras

Wambulwa still understands 16mm and 35mm cameras. While the cameras captured images, sound was recorded separately on a Nagra recorder using quarter-inch open-reel tapes—known as the double system.

These tapes were later transferred to sprocketed 16mm sound stock for editing and synced to picture using a clapper board.

Siminyu and his peers were well prepared when video arrived.

In the U-matic era, cameras and recorders were separate—cameramen handled the camera while soundmen carried the recorder. Then came the devastating shift: integrated camcorders. U-matic was phased out, replaced by Betacam, DVCAM, and later SD cards, discs, and SSD-based systems.

This miniaturization shrank production crews from two or three people to one person who could shoot, record sound, produce, and even edit.

Film Quality and Craft

“We lack the diversity that made us share ideas in the field,” Wambulwa says.

“Sound has been mutilated. The artistic part is gone.”

He recalls his synergy with Bwoka:

“If he planned to pan left to right, I knew where to stand so my microphone wouldn’t appear. We respected each other’s roles.”

Siminyu also fondly recalls Newsreel days.

“Bwoka taught me to love and care for equipment. That unit taught me to multitask.”

Film equipment was heavy.

“My sound recorder weighed around 15 kilos. I could be in the field for months. But once you got used to it, it was like going to the gym,” Wambulwa laughs.

He echoes Bwoka’s sentiments: 35mm and 70mm film yield superior images.

The narrower 16mm becomes grainy when projected large.

“But 35mm on a small screen? Beautiful picture and beautiful sound.”

Kenya never had a 35mm lab, but KIMC’s 16mm facility still worked well by 2016. Unfortunately, KBC’s processing equipment was dismantled and dumped at KIMC. He is unsure whether the Mombasa lab still exists.

Attempts at Revival

In 2006, President Mwai Kibaki sought to modernize film facilities. Wambulwa was among three experts sent to Waterfront Studios in South Africa.

They discovered Kenya needed only one key machine: a telecine, which would digitize 16mm or 35mm film after processing, enabling editing, sound syncing, and duplication.

“We submitted our report. I don’t know how far it went,” he says.

He believes revival now lies with policymakers.

“The people who made films are still there. They can advise.”

A Message to the Youth

Many archival films have badly faded.

If only the government could invest in preservation and production, he says.

His former colleague, laboratory instructor Eston Munyi, used to say:

“Pictures are seeing for keeps. Properly stored, motion pictures can last 100 years.”

Today, Wambulwa relies on subsistence farming—maize, bananas, sugarcane, livestock, and poultry. He keeps in touch with his old colleagues; many have retired, some have passed on.

His message to young filmmakers:

“As you prepare a story, think of the future. Films made long ago still speak today—look at Charlie Chaplin.”

But as film fades into memory, video thrives—and the arrival of still cameras capable of recording video has driven the final nail deeper.

By William Inganga